Proof of Concept: 20,000 Payments per Second with Checkpoint Replication

Jactl 1.3.0 introduces the ability to checkpoint the current execution state of a script and have it restored and resumed elsewhere after a failure. In order to test this new feature, I implemented a proof-of-concept project that simulates a payment processing system that accepts payment requests, performs some operations by interacting with multiple external systems and then returns a response.

The payment processing system checkpoints its state when required and if a failure occurs, payments in flight will have their state restored and resumed to make sure that no payment is lost.

Jactl Checkpoints

Jactl is a open source scripting language intended to be embedded into real-time Java applications. It doesn't itself offer any mechanism for persisting or replicating the checkpoint state but, instead, provides hooks that need to be implemented by the application if the checkpoints are to be persisted or replicated. These hooks allow the application to know when a new checkpoint has been generated for a running script and when a running script instance has finished (which allows the application to then delete any checkpoints for that instance that had been created). There is also a hook for the application to use when recovering after a failure to tell Jactl to restore a script instance and resume its execution from where it left off.

Since Jactl scripts never block (from a Java thread point of view), whenever a script invokes a function that would

otherwise block, such as sending a request to a remote system and needing to wait for a response, or reading some

data from a database, Jactl captures the current execution state in a Continuation object (actually a chain of

Continuation objects; one per stack frame) and when the response is ready to be processed the execution state is

resumed.

The checkpoint feature is just a simple extension of this existing mechanism.

When a script instance invokes the checkpoint() function, the current state is captured in these Continuation

objects which encapsulate where in each stack frame the script is up to, and the values of any local variables.

The checkpoint state is just an encoding of all this information into an array of bytes.

This array of bytes can then be stored or sent over a network and later passed into the Jactl runtime to restore the script instance state and continue execution from where it had been checkpointed.

NATS Messaging

To implement a proof-of-concept of the checkpoint facility, I used the publish/subscribe mechanism provided by the NATS messaging infrastructure. I wrote a generic Jactl Server that takes a directory of Jactl scripts and for each script listens on a NATS topic of the same name and then provided it with a Jactl script for processing payment requests.

NATS allows multiple instances of an application to listen on the same topic and will automatically spread the load across those instances. Clients can then send requests to a topic and NATS will forward it to one of the instances subscribed to that topic.

Note that although NATS also supports reliable message streams (called JetStream), this was not used for this project. Since we are checkpointing our state when necessary, we rely on the checkpointing to provide reliability and use standard NATS messaging without any reliability guarantees.

All messages between the different components were encoded in JSON using the native JSON support provided by Jactl.

Kubernetes

To make it easy to scale up multiple application instances, I deployed the payment processor instances and the simulators (including the load generator and the simulators for the external systems) in a Kubernetes cluster and captured metrics in Prometheus that I could then view in Grafana.

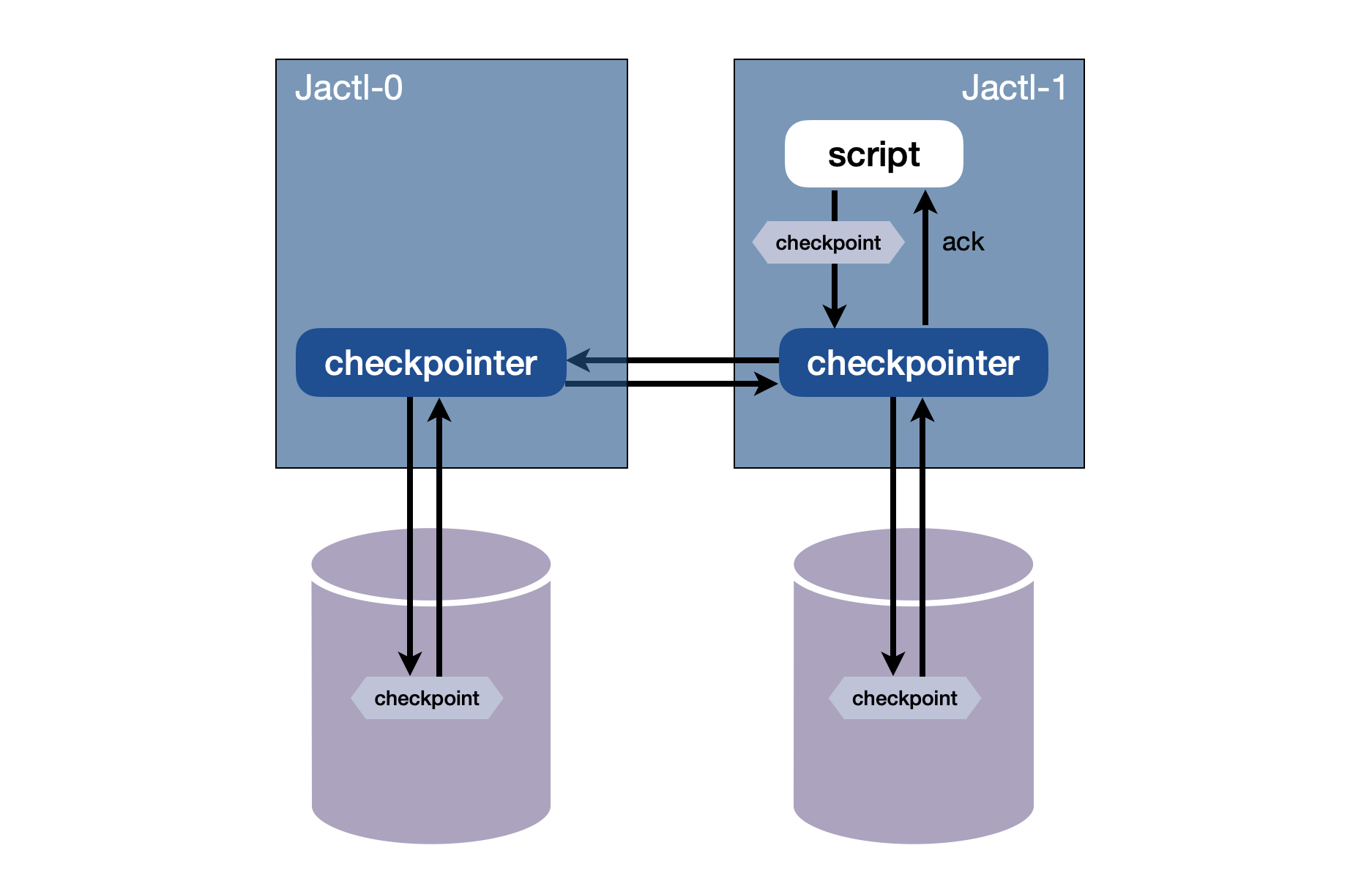

Checkpoint Persistence, Replication, and Recovery

For the proof-of-concept I decided to write the checkpoints locally to volumes attached to each application instance. The volumes are handled by Kubernetes and are attached to the pods (the application instances) when they are started. If a pod dies, it will be restarted by Kubernetes, and it will be given the same persistent volume as before.

In order to provide additional fault tolerance, the checkpoints, as well as being written locally to the file system belonging to that pod instance, are replicated to another pod instance where they are also stored in the file system belonging to that instance. The concept is that this other instance could be located in another data center and so this provides a disaster recovery mechanism in case the entire data center is lost (including the disks containing the pod file systems).

When checkpointing, the script instance waits for an acknowledgement that the state has been stored locally as well as waiting for an acknowledgement from its replication peer that the state has been replicated and stored remotely before continuing. (If the remote instance is down then the script will just persist locally and won't wait for the remote replication.)

For the purposes of the proof-of-concept, the application is deployed as a StatefulSet and is deployed as Jactl-0,

Jactl-1, Jactl-2, and Jactl-3, and the pods always connect to their peer in pairs: Jactl-0 with Jactl-1,

Jactl-2 with Jactl-3, and so on.

Checkpoints are replicated in both directions between each of the instances in a pair.

Recovery of checkpoints is done whenever an application instance starts up. The first thing it does is read the checkpoints in the local file system and find all non-terminated script instances, restores these instances, and resumes their execution. During start up it also request its replication peer to send it the current set of checkpoints for the executing script instances on the peer in order that it can persist these locally.

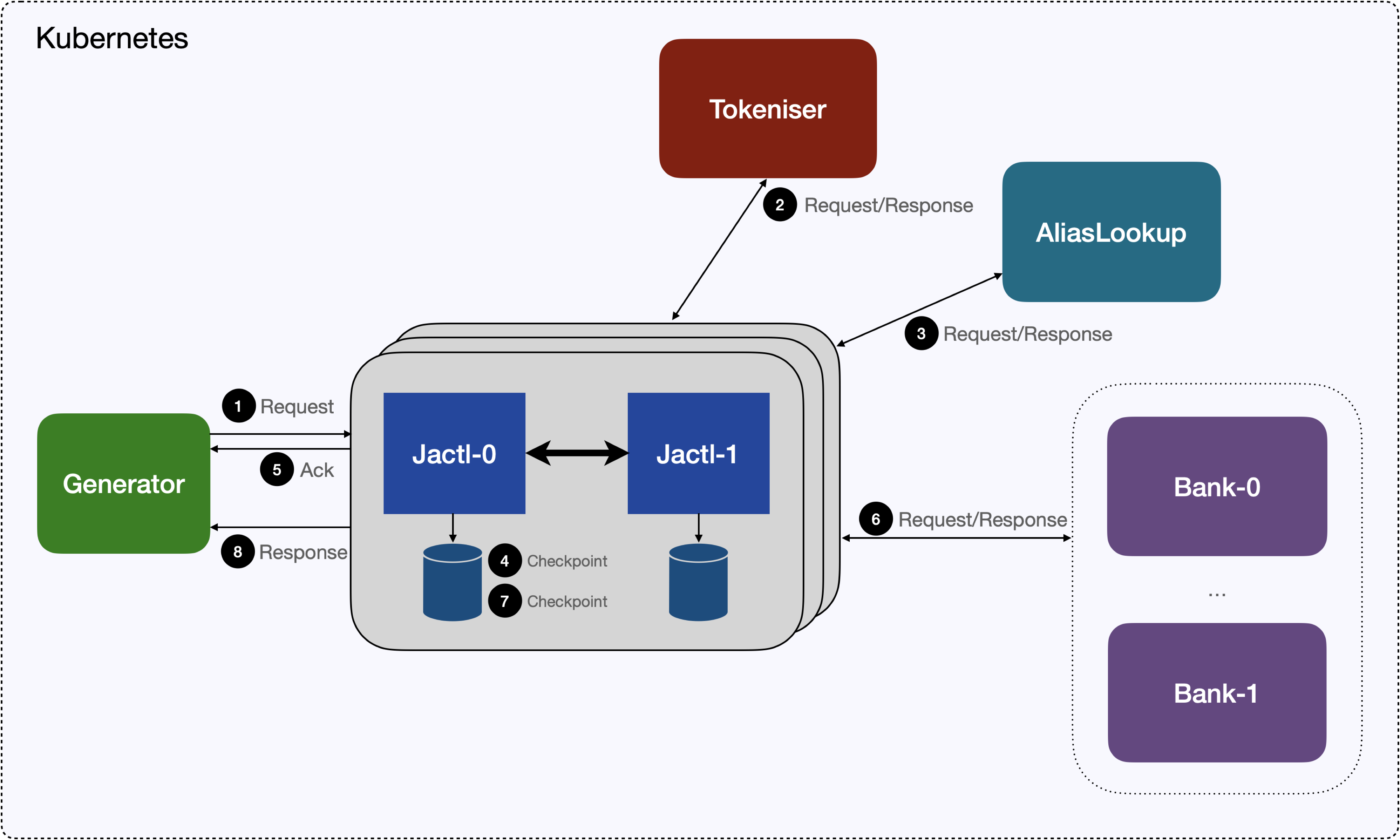

Payment Flow

For the purposes of the simulation, the Jactl-x pods that are processing the payment requests, simulate a callout

to a Tokeniser service that transforms the credit card or account number into a token for security purposes, then does

an Alias Lookup via a callout to another external system to find the destination bank to which the payment authorisation

needs to be sent, sends the authorisation, and then responds back with the result.

The payment application does an early acknowledgement back to the requester once it has a token and has done the alias lookup and we checkpoint our state at this point. The caller therefore knows that once it gets that early acknowledgement there is a guarantee that the payment will be processed even if a failure later occurs.

We also checkpoint our state after getting the response from the bank.

The payment flow is shown in the following diagram:

The payment flow has the following steps:

- The load generator sends the initial payment request and NATS delivers it to one of the

Jactl-xpods. For this particular test the number of instances was scaled to 4. - The payment simulator (

Jactl-xinstance) sends a request to theTokeniserto tokenise the card number/account number and waits for the response. - The payment simulator then sends a request to the

Alias Lookupservice to lookup what destination bank to send to and waits for the response. - The payment simulator checkpoints the state of that payment processing script instance.

- An early acknowledgement response is sent back to the payment generator.

- The payment authorisation request is sent to the

Bank-xinstance that corresponds to the bank returned during the alias lookup and waits for the response. - The payment simulator checkpoints the payment state.

- A final response is sent back to the payment generator.

Simulation Results

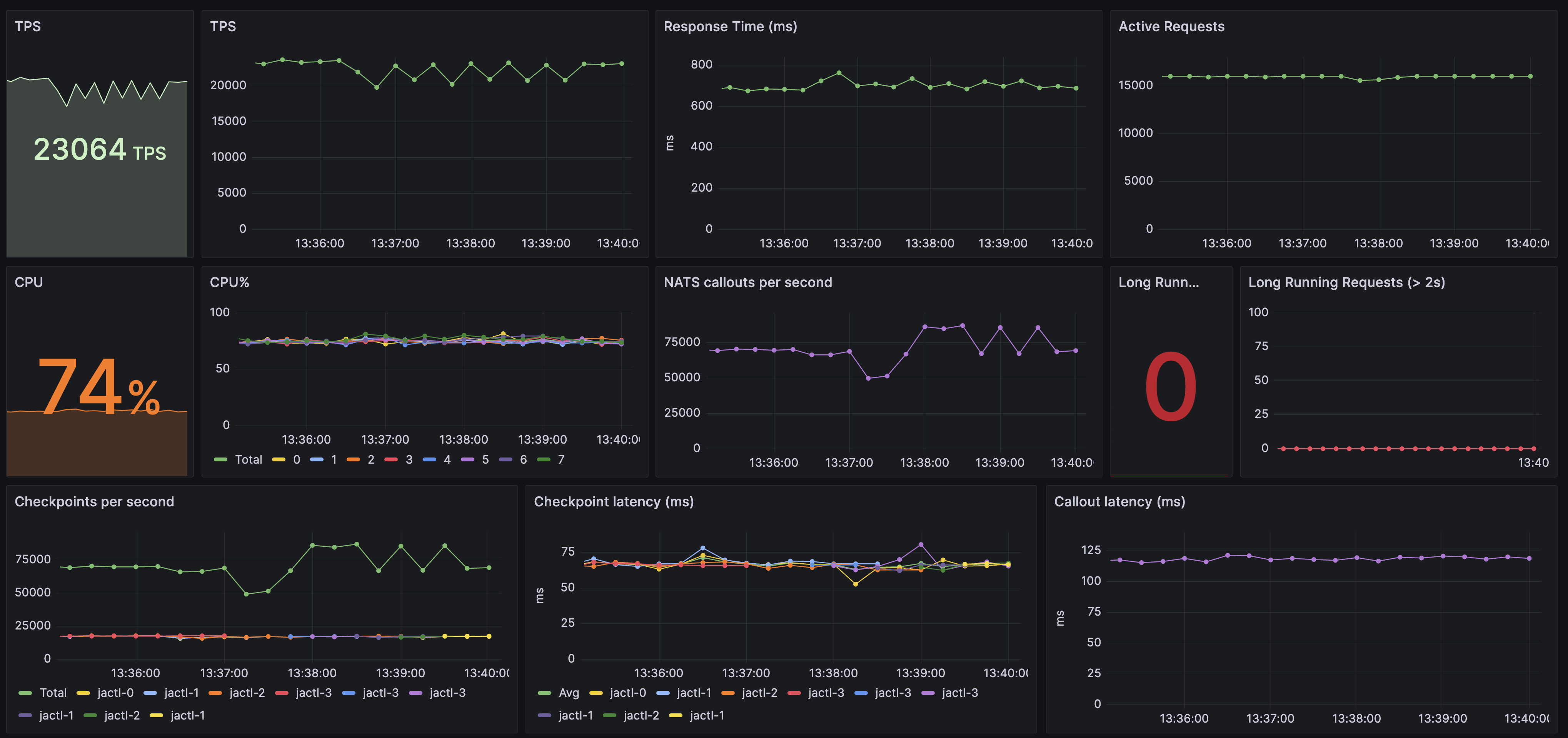

As noted, I ran the simulation in a Kubernetes cluster. This particular Kubernetes cluster ran entirely on my laptop, running on 8 cores.

While running the payment simulation I randomly killed the Jactl-x pods to see how restarting failed pods and

going through recovery would affect the throughput.

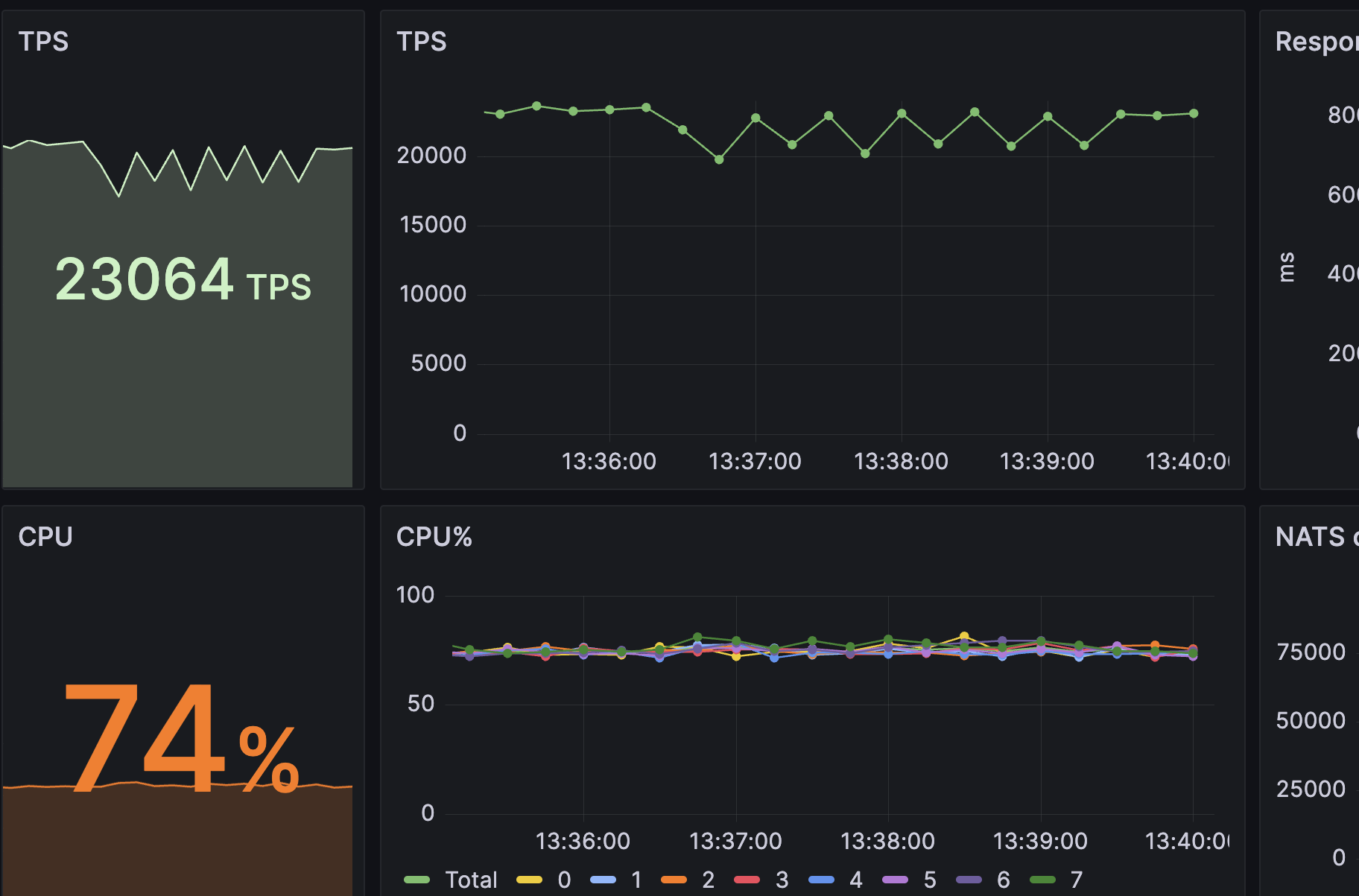

Here is a snapshot of the Grafana dashboard showing the payment processing rate (TPS):

The TPS graph shows a sawtooth-like pattern during around 3 minutes where the TPS momentarily dips slightly every 30 seconds or so.

This is the period during which I was randomly killing a Jactl-x pod every 30 seconds.

As the graph shows, the impact of the pod failures on the throughput was pretty minor:

On the dashboard shown there is also a graph of "Long Running Requests" showing if there are any long-running payments (from the payment load generator's point of view). This shows the number of payments where the early acknowledgement has been received but for which the final response has still not been received after 2 seconds. If there was a problem with recovering script execution state after a failure then we would expect to see this count be non-zero. Given that it remains at zero for the entire run it shows that all such payments were recovered and completed successfully.

Further Reading

For information about Jactl, see the Jactl documentation web-site.

The project is hosted on github.